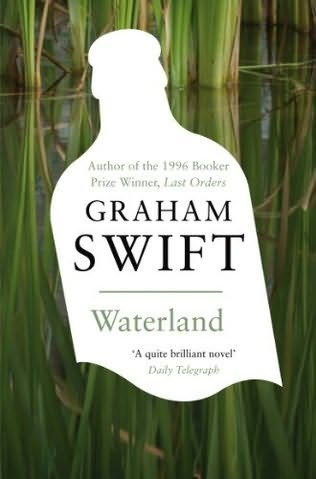

The very best novels I have read have changed me: they have changed the way I think; they have changed the way I write; and they have changed the way I live. This might sound like an exaggeration, but it is not. One of the novels to have this profound effect on me was Waterland by Graham Swift. Written in 1983, I first read it in 1996, whilst I was travelling in South East Asia. I spent several weeks staying in a tiny guest house on stilts above the waters of the estuary of the Terrenganau river on the north-east of the Malay peninsula, and every waking (and sleeping) moment of mine was spent with the sounds and the smells and the sight of this vast waterway overwhelming my senses. It couldn't have been a more apt place, therefore, to read this novel, about a History teacher who grew up in the Norfolk fens, beside the river Ouse, and whose life was permeated by the 'spirit' of that river, ever since he discovered in it the dead body of one of his friends. It's part thriller - and part 'coming of age' novel, but the most extraordinary thing for me was the way in which the story was TOLD, with a narrative which lulled me and hypnotised me with its freshness, originality and almost musical command of the written word and, above all, the art of storytelling. There's always a danger recommending something THIS highly, for fear you might be disappointed. But I am recommending it nonetheless. These are the opening paragraphs:

"And don't forget," my father would say, as if he expected me at any moment to up and leave to seek my fortune in the wide world, "whatever you learn about people, however bad they turn out, each one of them has a heart, and each one of them was once a tiny baby sucking his mother's milk..."

Fairy-tale words; fairy-tale advice. But we lived in a fairy-tale place. In a lock-keeper's cottage, by a river, in the middle of the Fens. Far away from the wide world. And my father, who was a superstitious man, liked to do things in such a way as to make them seem magical and occult. So he would always set his eel traps at night. Not because eel traps cannot be set by day, but because the mystery of the darkness appealed to him. And one night, in midsummer, in 1937, we went with him, Dick and I, to set traps near Stott's Bridge. It was hot and windless. When the traps had been set we lay back on the riverbank. Dick was fourteen and I was ten. The pumps were tump-tumping, as they do, incessantly, so that you scarcely notice them, all over the Fens, and frogs were croaking in the ditches. Up above, the sky swarmed with stars which seemed to multiply as we looked at them. And as we lay, Dad said: "Do you know what the stars are? They are the silver dust of God's blessing. They are little broken-off bits of heaven. God cast them down to fall on us. But when he saw how wicked we were, he changed his mind and ordered the stars to stop. Which is why they hang in the sky but seem as though at any time they might drop...

No comments:

Post a Comment